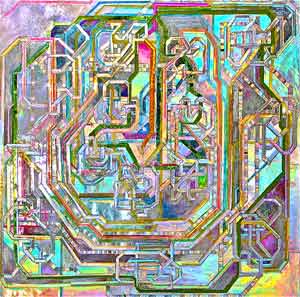

n°1 Entrelac de 3 labyrinthes

n°2 Ciel au fond d'un puit

n°3 Rencontre de 3 labyrinthes

n°4 Genèse du labyrinthe

n° 5 Khora

n° 6 Escalier et labyrinthe

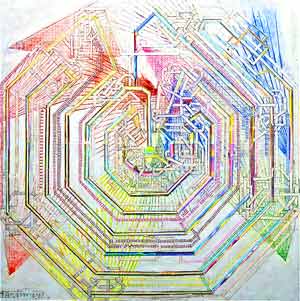

n°7 Tour de babel

n° 8 L'homme du 8e jour

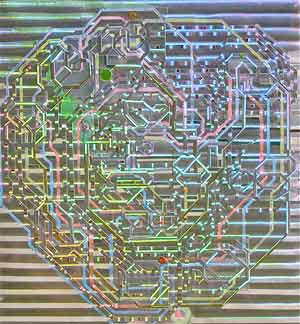

n°9 Rencontre du labyrinthe islamique et crétois

n° 10 Jérusalem céleste

n°11 La partie de go

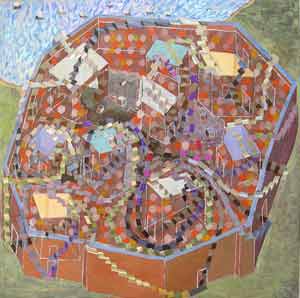

n°12 Temple labyrinthe

n°13 Où va le vide

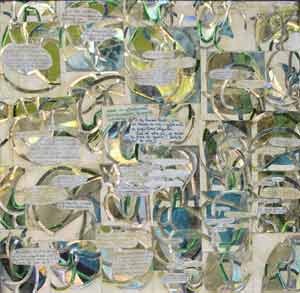

n°14 Voyage de Mercier et Camier

Samuel Beckett

n° 15 Petite musique des sphères